Turkish Kurds go home to war-ravaged city of Diyarbakir as curfew lifted

Hadi Bayram’s eyes fill with tears. “Rockets here, bullets there,” the baker says, gesturing at the damage to his modest premises located within the historic district of Sur, in the city of Diyarbakir in south-east Turkey. As he kneels in the rubble, harsh sunlight illuminates the shards of glass scattered around the building that has housed his business for decades.

The scene of a battle between Turkish security forces and fighters with links to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), Mr Bayram’s bakery is just another mound of concrete, metal and glass that was once an integral part of life in the traditionally Kurdish neighbourhood.

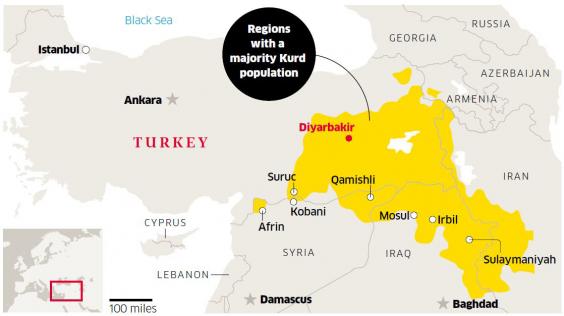

For months, conflict has been a constant feature of life in Diyarbakir and across south-east Turkey, the latest bloody episode in an fight for Kurdish autonomy by the PKK that can be traced back to 1984.

The Turkish state deem the PKK a terrorist organisation, as do a number of Western states, and in December, government forces imposed a 24-hour curfew across a number of areas in the south-east as part of military operations carried out against the group.

The curfew in Sur is now gradually being lifted street by street. For those who managed to flee the fighting to other areas of the country, it has allowed them finally to come home, while those who stayed now have a chance to assess the damage to their property.

The issue of burials is also fresh in the minds of many. In one part of Sur, families gather each day inside Diyarbakir’s Dicle Firat Cultural Centre, and a protest takes place. Relatives of those killed in the conflict clutch pictures of loved ones, asking the Turkish government to give back the bodies of those killed in the fighting.

Sakir Gokalp is one of these people. “When I went to the morgue to find my brother it was impossible. One boy was run over by a tank, he was like minced meat. I feel like crying, but what can I do? It’s hopeless. No one will help us,”

Mr Gokalp’s brother was killed fighting in Sur as part of the PKK. He was 18. Two weeks ago, Mr Gokalp’s father got a call saying his son had been killed in the violent clashes between Turkish special forces Kurdish fighters, many of them young men. “We were looking for him for a long time. We thought he was in Iraq or Syria but it turned out he was fighting here in Sur, a district not far from our home,” Mr Gokalp explains, as weeping women pray nearby.

This latest outbreak of fighting between the PKK and Turkish forces is one of the bloodiest since the 1990s, and comes after the breakdown of a fragile peace. In March 2013, the jailed PKK leader, Abdullah Ocalan, had called for a ceasefire after negotiations with the government of Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the then prime minister and now president. That finally collapsed in July 2015. The current military operations and curfews in the south-east of Turkey have been described as a “collective punishment” by human rights group Amnesty International.

Andrew Gardner, a researcher on Turkey for Amnesty International, was refused access to Sur while trying to gather data on the curfews last December.

“There are two areas of concern here. One is the curfews, which amount to collective punishment; and the second is use of force,” he said. “The violence has escalated and we’re seeing an increase in the use of heavy weaponry as curfews are extended. We estimate about 300,000 people have been forcibly displaced by the conflict.”

As the military operations move from one region to the next, the fragile peace of 2013 seems a distant memory. Turkish soldiers patrol Kurdish neighbourhoods under curfews – right now there are curfews in seven Kurdish districts and cities scattered around the south-east. Those who lived under the curfew in Sur have told of food shortages and lack of water, as tanks and snipers searched for PKK fighters in Sur’s winding streets, which are surrounded by an ancient wall.

There have also been dozens of civilian deaths during the military operations in recent months, although the Turkish government have repeatedly denied suggestions that is has been deliberately targeting residents. The decision by PKK fighters to create trenches and dig in within a number of areas has also helped to create a situation where civilians are in danger.

Matters have been further complicated for the government by the conflict in neighbouring Syria, which has helped to create the worst refugee crisis in decades and also given Mr Erdogan a number of problems. The success of Syrian Kurdish forces linked to the PKK in fighting Islamic State has deeply unnerved Turkey’s political leadership and the military. It has also complicated the relationship between Ankara and its Western allies such as the US, which, despite deeming the PKK a terrorist organisation, has supplied arms to its offshoot in Syria.

independent.co.uk